Kazan University during First World War: Arbuzov’s aspirin and women’s courses

The Day of Remembrance of Russian of World War I is celebrated today, August 1. We tell you how Kazan University became a “university for the front” and why Russian science develop even in such a tragic period.

Tanks, mortars and grenade launchers, submarines, chemical shells, aviation and other unique – for that time – types of weapons and equipment were used during the war. Basically, says Andrei Afanasyev, a storage specialist of the History Museum of Kazan University, such engineering innovations were common in the armies of our country’s allies and the enemy’s. In Russia, however, technical universities in Moscow and St. Petersburg were assigned such objectives, so Kazan University was given another – to provide the front with medical personnel.

“If we look at the admission of students in 1913-1914, we will see that more than 50 percent of them entered the medical faculty. At that time it was the most popular in the university, and it had been so since the end of the 19th century. Therefore, the government thought that our university should train medical personnel and become a refuge for wounded soldiers. The war began on July 19 (Julian calendar), and on July 28 the University Council informed the Emperor about its readiness to help the Fatherland. Thus, the university was ready to give part of its premises for hospitals and infirmaries,” Afanasyev explains.

Hospitals were set up in the university’s main building on Voskresenskaya Street (now 18 Kremlyovskaya Street, the Main Building), in a three-story clinic building on Poperechno-Klinicheskaya Street (now one of the KFU buildings on Nuzhina Street, 1) and in other clinics located in the city center. In parallel, courses were organized to train medical workers to be sent to the front, in particular, a two-month course for female nurses was very popular among the townspeople.

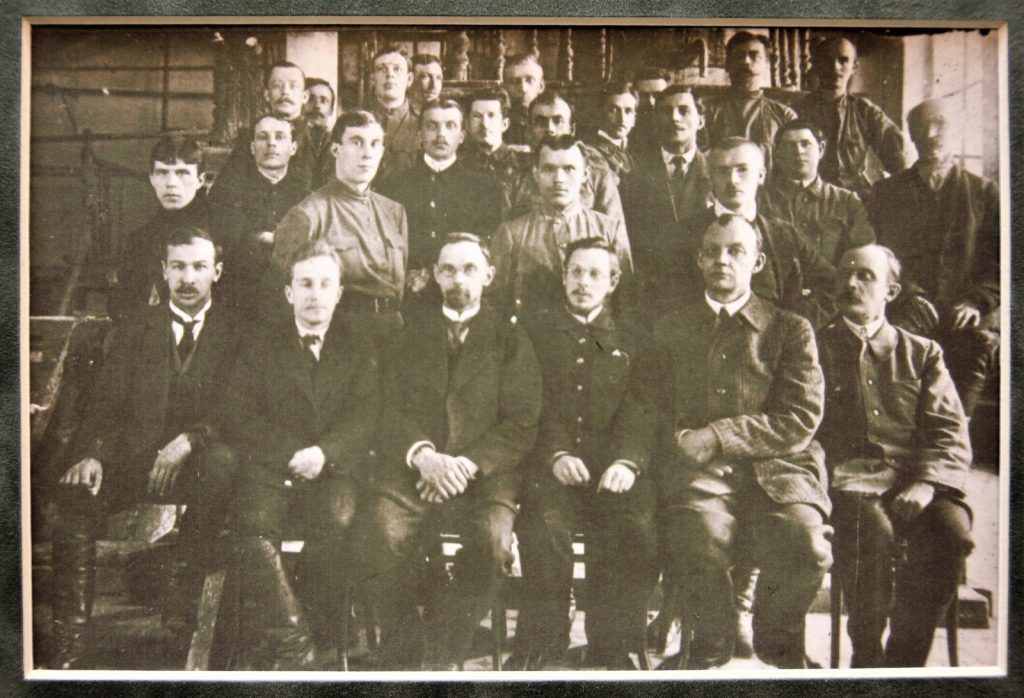

“During the first year of the war, from July 1914 to July 1915, the university trained 260 nurses, of whom 170 went to military hospitals. Many medical professors and young specialists also went to the front,” says the expert.

The most famous of the field doctors was Professor Boris Lavrentyev (1892-1944), who later became a corresponding member of the USSR Academy of Sciences. Lavrentyev is considered one of the founders of Russian neurosurgery, a major specialist in neurohistology. In 1941 the doctor was awarded the Stalin Prize.

Students also went to the front. G.T. Titov, a student of the Faculty of History and Philology, and I.G. Beilin, a graduate of the Faculty of Physics and Mathematics, served in the rank of lieutenant, and the second was awarded two St. George’s Crosses, the main military award of the time. In the fifth year of the medical faculty student P.G. Peterson joined the ranks of soldiers. D.K. Popov, a law student, and A.F. Nagevich, a graduate of the Physics Department, also became participants of the war. It is known that the latter did not return from the Austrian front.

“At that time there was really no deferment. Students were drafted to the front, and many served on their own initiative. They canceled the draft for students only in 1916, on February 8,” Afanasyev notes. “In the fall of 1914, a black board was installed in the assembly hall of the university, on which the names of those who perished were written down”.

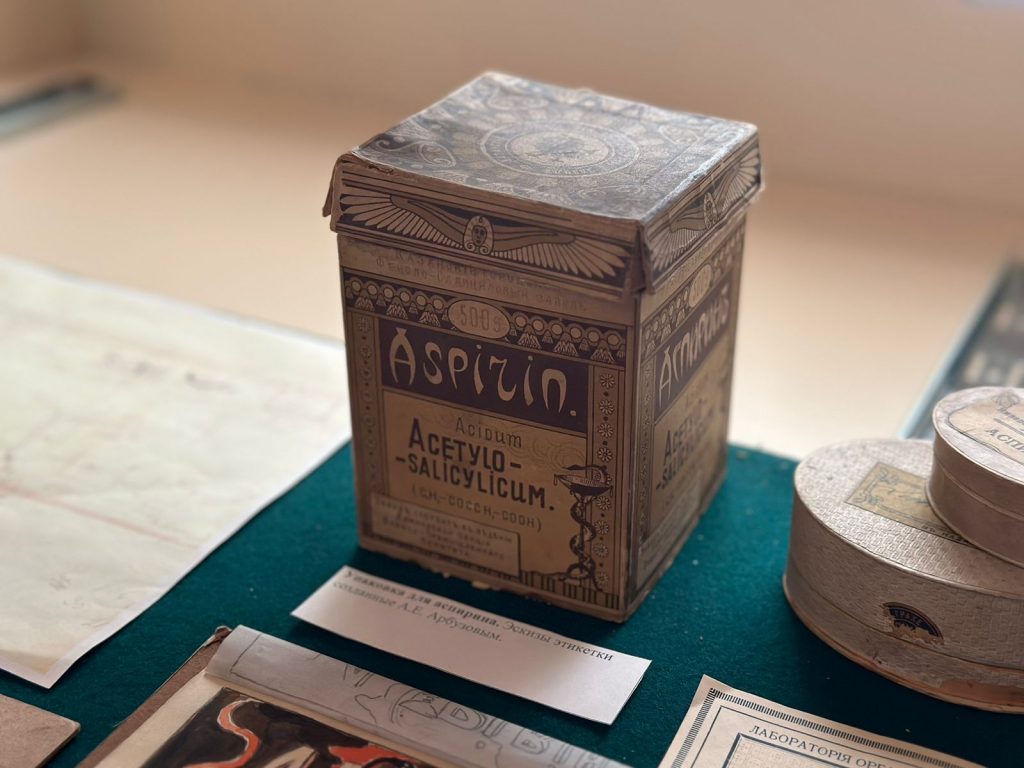

As soon as World War I started, Russia stopped importing medicines, as at that time they came mainly from abroad. The question of import substitution of aspirin arose. In 1915, with the assistance of Kazan University professor Alexander Arbuzov, the problem was solved at the factory of the Krestovnikov brothers in Kazan. They opened a phenol-salicylic plant at one of the premises.

“It was the Russian analog of aspirin that was first produced on an industrial scale in 1915. The label from this aspirin and its poster are still kept to this day in the Museum of the Kazan Chemical School. In the best years they produced up to 16 kilograms of aspirin per day. Almost all aspirin was sent to the frontline,” Afanasyev shares. “During World War I, chemical weapons began to be tested. Professor Alexei Bogorodskii participated in the development of methods of defense against these gases. He was looking for a substance that would prevent chemical weapons from passing through the glass of a gas mask. At the university in 1915, a special commission was even created to develop protection against chemical weapons. It included both physicians and chemists, including chemists Alexander Arbuzov, Flavian Flavitskii, Alexei Bogorodskii, as well as physicist Dmitrii Goldgammer and prominent surgeon Alexander Vishnevskii.”

The University Council regularly sent money to the Red Cross. It is documented that students Yerofeev and Stolov traveled to the front in December 1915 to deliver humanitarian aid to soldiers.

“In October 1914, the students marched with a demonstration through Kazan, holding portraits of Emperor Nicholas II, flags and banners of our country and the Allies, they reached the Governor’s Palace in the Kremlin. The governor handed the emperor their petition, which stated that the university supported the sovereign in every possible way and hoped that victory would remain on their side. The emperor sent a telegram in response, ‘accepting’ their solidarity,” Afanasyev said.

During the war years, according to the interlocutor, Kazan University became the first university in Russia to open higher education for women. The university’s decision to admit women as students, and not as free listeners as before, was due to a sharp decrease in the number of students. If in 1913 Kazan University trained 2,012 students, then 4 years later, in 1917, their number decreased to 1,859. Many went to the front right from the student bench, and someone immediately after graduating from the high school.

“In the fall of 1914, the Council of the Faculty of Physics and Mathematics made a proposal that women should be allowed to enroll. And only a year later, in August 1915, there was a government decree that Kazan University at the Faculty of Physics and Mathematics, the Faculty of Medicine, and a little later at the Faculty of Law allowed the admission of the first female students. And this was the starting point of official higher education for women in Russia,” concludes the interviewee.