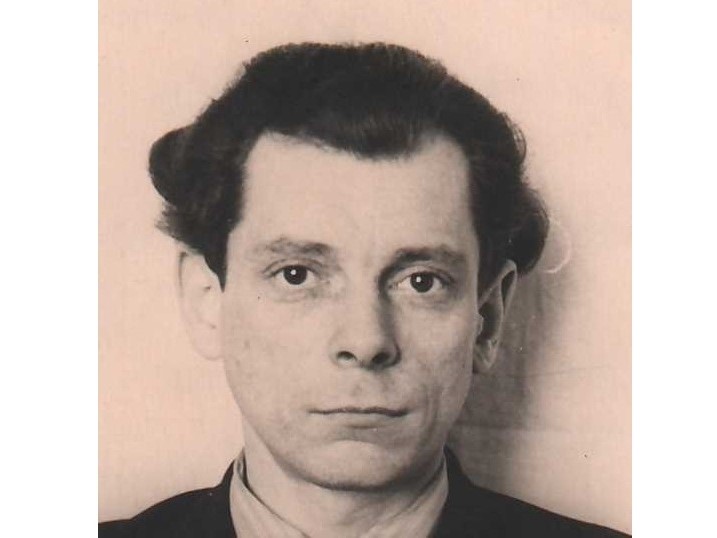

Scientific Regiment: Gleb Pokrovsky recalling his years as reconnaissance officer

On the 82nd anniversary of Nazi Germany’s invasion, KFU continues to tell the stories of war heroes who studied and worked at the University.

Gleb Pokrovsky was born in 1925. In 1941 he graduated from eight grades of high school in the city of Leningrad. The young man was in the city when it was cut off from the whole country on September 8. The 900-day blockade began. The most terrible time of the blockade was the autumn-winter of 1941-1942. There were bombardments, hunger, and cold. But the city lived, and its enterprises, clinics, kindergartens and schools kept working.

Pokrovsky wanted to volunteer at the front, and after a short training as a radio operator in March 1943, he was thrown into the German rear, in a partisan detachment. He fought in the 11th Volkhov brigade at the Leningrad Front, then at the Baltic Front. In memory of that terrible and cruel war, which took the lives of many people, he wrote memoirs.

“In 1943 I was in Grigory Grigoriev’s unit. There were 36 of us. When thrown into the rear, our detachments were called NKVD reconnaissance-sabotage detachments, not partisan detachments. Our tasks were: reconnaissance on railroads and highways, organization of sabotage, communication with residents. It was categorically forbidden to accept civilians and renegades in the detachment, as well as to enter villages and settlements. Weapons, ammunition and food were dropped from airplanes.

“I served as a radio operator. The unit’s area of operation was limited to the Vitebsk and Warsaw railroads, and to the south, to the Luga-Novgorod railroad. There was no permanent place of deployment. We had to change our resting places all the time. No dugouts. We usually settled down for the night in the dense woods. We piled fir-tree brushwood on the ground and covered ourselves with ground cloth.

“During the breaks we organized all-round defense. Groups were arranged in a circle around the headquarters, and sentries were posted. The day usually began at dawn. After washing in a nearby puddle we started to prepare breakfast. To avoid building several fires we cooked food with the bowlers on ‘fishing rods’ – long sticks with a hook at the end. This allowed five or six pots to be heated simultaneously on one fire. If there was a good supply of food, canned goods and oil were added to the cereal soup. Porridge, as a rule, was not cooked: too much work.

“Our main task was to organize derailments on railroads. Suffice it to say that during one summer month of 1943 groups of the detachment derailed 17 enemy trains. From the beginning of the battle at Kursk Salient all the detachments were given a directive to maximize sabotage work – to undermine rails, to cut down telegraph poles in order to complicate the transfer of Germans to the south. At that time I and other radio operators had to transmit a huge volume of material – information about the number of trains, their cargoes, about the changes in the disposition of the units. Sometimes I had to go with groups on different missions. Usually radio operators were sent on long journeys in order to report to the headquarters of the guerrilla movement as quickly as possible the information and results of their work.

“Sometime at the end of April we received an order from headquarters: to unite separate detachments in our area into the Volkhov Brigade for more effective work in the rear. On the island, where we came, there was a dense pine forest: tall trees, one and a half to two girths high. We built firing points out of boulders and mined all the approaches to the camp, for the good there was no shortage of chalk. The camp was called a stone camp. There were even anti-rock mines: a camouflaged cable of parachute straps was led to the charges of 15-20 kg of TNT. In order for such a mine to go off, it was enough to pull the cord.

“In mid-July the assault on the camp began. During the day the Germans made nine attacks and suffered great losses. There were only two wounded in our brigade. By the evening we were running out of ammunition. We decided to leave the encirclement. We poured ammunition into the fires, set mines to create a semblance of firing, and all the detachments went around the German ring from the north, up to their necks in the impassable swamp. The punctilious Germans, believing the maps, did not bother to encircle us from the west, believing that the marshes were sufficient. As we were already on solid ground, we heard gunfire and explosions: it was the Germans bursting into the camp.

“The brigade split into squads and began to leave the area to the south, while the Germans began combing the forest. The forest quarter was cordoned off on three sides, with soldiers stationed 20-30 meters away. On the fourth side, SS soldiers were coming, firing machine guns. Grigoriev managed to lead out almost his entire squad. The Germans were chasing us for three days. Completely exhausted, we lay down in some wood, put sentries and fell asleep. We were almost surrounded, and if it were not for Grigoriev, who woke up and noticed the Germans and raised the alarm, we would have been killed. I woke up from the terrible shooting, got down on all fours and only had time to put the radio belt around my neck when I got a hard blow. I felt no pain yet, but both arms were hanging around helplessly. I ran towards the direction from where the shots had not been fired from, saw the fresh trail of the people who had just run by and rushed after. On the way I met Novozhilov, one of the squad leaders. He was facing in the direction from where the Germans could appear, called me, put a tablet around my neck and told me to give it to Grigoriev. I called out to him with it, but he pulled his pistol from his holster. When I looked back, I saw that his whole back was covered in blood. How could he still be on his feet? When I ran a little away, I heard a shot. I was running so fast, I probably would have earned a medal in a competition. When I heard my feet stomping ahead of me, I yelled, and the group stopped. Of the 34 people who had been in the group before, only half remained. Nurse Katya hastily bandaged my wounds. It turned out that I had been wounded in my back and right arm. The entry wound of the bullet was opposite my heart, but because I was on all fours at the time of the wound, the bullet had gone through my ribs. It fractured my left clavicle and lodged in my shoulder. Both hands were tied with a bandage around my neck and we ran on. While crossing the railroad between Luga and Novgorod, the Germans found us again and opened fire. Having dispersed, we ran further. We took cover in a large wooded area about a hundred kilometers south of our old base. The situation was desperate. We were out of food supplies. We fed on grass – hare’s cabbage, caught frogs and grasshoppers. We began to faint from hunger. We were running out of ammunition and, most importantly, of food for our radio set. Connecting several batteries we hardly managed to reach the headquarters. Towards the autumn we were finally allowed to take civilians. Many young people from the villages came. At the same time, as a rule, in groups, the Vlasovites began to join us. Most of them justified our trust.

“With the beginning of the offensive near Leningrad in January 1944, the headquarters of the partisan movement issued an order: to disrupt all German transports to the front, destroy communications, roads, and garrisons. But the Germans had no more time for us: things were getting worse and worse for them at the front…”

Pokrovsky finished the war in Lithuania, took part in the defeat of the Kurland group of the enemy. After the end of the Great Patriotic War, he served in the group of Soviet troops in Germany, and was demobilized in 1951.

In 1952, he graduated with a gold medal from evening school and then entered the Physics and Mathematics Faculty of Kazan University. He worked as an engineer, a teacher, in 1973 Gleb Pokrovsky defended his thesis for the degree of Candidate of Physics and Mathematics. He taught at the Department of Radio Astronomy.

The war hero retired from the University in 2001. Among his commendations were Order of the Patriotic War of the 1st degree, medals “For Courage”, “Partisan of the Patriotic War” of the 2nd degree, “For the Defense of Leningrad” and others.